Criteria for the Use, Processing, and Disposal of Flexible Endoscope Cleaning Brushes

Abstract

Objectives: To ensure effectiveness in the endoscope channel cleaning process, using functional brushes that are in good condition is necessary. This study sought to identify the criteria for acquiring, using, and disposing of cleaning brushes at endoscopy facilities in Brazil. We further sought to evaluate the conditions of the cleaning brushes in use in the facilities.

Methods: This cross-sectional study was conducted between July 2021 and January 2022. Personnel responsible for processing endoscopes were interviewed regarding the use, processing, and disposal of flexible endoscope cleaning brushes. In addition, the brushes used to clean the equipment were inspected.

Results: All participants interviewed reported the practice of brushing endoscope channels. Of them, 60% noted the use of disposable brushes, with 40% using reusable brushes. None of the facilities interviewed reported discarding disposable brushes after use. The protocols for disposal of brushes included disposing due to bristle wear (70%), disposal at the end of the day (20%), and an absence of disposal protocols (10%). In addition, 30% of facilities did not clean the bristles before reintroducing them into the channel/lumen, and no facility had an established routine for cleaning brushes between uses. Inspection of brushes revealed that only 20% of facilities had new brushes with no signs of wear or damage.

Conclusion: The use of inappropriate brushes/sponges for cleaning endoscope channels and the lack of criteria for the reuse and disposal of brushes increases the risk of cross-contamination, internal damage to channels, and biofilm formation.

Abstract

Objectives: To ensure effectiveness in the endoscope channel cleaning process, using functional brushes that are in good condition is necessary. This study sought to identify the criteria for acquiring, using, and disposing of cleaning brushes at endoscopy facilities in Brazil. We further sought to evaluate the conditions of the cleaning brushes in use in the facilities.

Methods: This cross-sectional study was conducted between July 2021 and January 2022. Personnel responsible for processing endoscopes were interviewed regarding the use, processing, and disposal of flexible endoscope cleaning brushes. In addition, the brushes used to clean the equipment were inspected.

Results: All participants interviewed reported the practice of brushing endoscope channels. Of them, 60% noted the use of disposable brushes, with 40% using reusable brushes. None of the facilities interviewed reported discarding disposable brushes after use. The protocols for disposal of brushes included disposing due to bristle wear (70%), disposal at the end of the day (20%), and an absence of disposal protocols (10%). In addition, 30% of facilities did not clean the bristles before reintroducing them into the channel/lumen, and no facility had an established routine for cleaning brushes between uses. Inspection of brushes revealed that only 20% of facilities had new brushes with no signs of wear or damage.

Conclusion: The use of inappropriate brushes/sponges for cleaning endoscope channels and the lack of criteria for the reuse and disposal of brushes increases the risk of cross-contamination, internal damage to channels, and biofilm formation.

Cleaning is a critical step in the safe processing of gastrointestinal endoscopes.1 Gastrointestinal endoscopes have a complex structure and become highly contaminated during use.2,3 Failure to brush the channels, damage that is not perceptible in clinical use or during processing, and inadequate training of operational staff are factors that contribute to the transmission of pathogens among equipment users.4–7

Brushing is an essential step in the cleaning of flexible endoscopes. This step is dependent on the operator and can be impaired by external factors, including pressure to clean equipment quickly so it can be returned to patient care, the force used in cleaning, inattention to detail, inadequate time spent cleaning, poor training, and omission of proper cleaning due to lack of knowledge of or commitment to the importance of the activity.7–9

Brushes of varying size are needed based on the diameter of the lumen in which they will be used. Therefore, it is necessary to consider the structure, diameter, and length of brushes, in order to promote the removal of the residue without causing grooves or damage to the internal surface of the equipment.1,5,10–12

Current processing guidelines recommend using single-use (disposable) cleaning brushes.7,11,12 However, in clinical practice, brushes commonly are reused without well-established criteria for reuse.8 This practice can cause damage and the release of brush bristles, leading to brushes not fulfilling the essential function of removing residue. In addition, the possibility for cross-contamination exists, potentially resulting in the transfer of microorganisms between equipment. This can compromise the effectiveness of processing, especially during cleaning and subsequent phases.5,7,10,13

Therefore, brushes can be considered potential vehicles for transmitting microorganisms, as they encounter a high microbial load during use.2 In addition, if no decontamination methods are used between uses of brushes, the risks of cross-contamination by microorganisms and biofilm formation are increased.7,14,15

Objectives

This study sought to evaluate the acquisition, use, and disposal of cleaning brushes at endoscopy facilities in Brazil. The condition of the brushes used was assessed via interviews with the professionals responsible for processing, followed by inspection of the brushes available in the cleaning area.

Methods

Approval to conduct this cross-sectional study was obtained from the research ethics committee of the Federal University of Minas Gerais (COEP-UFMG; opinion no. 4866688). The study was conducted in endoscopy facilities in the city of Belo Horizonte, Brazil, from July 2021 to January 2022. A search of Brazil’s CNES Datasus system identified 82 active facilities. After excluding duplicate records and out-of-town addresses, 51 facilities remained. They were contacted by phone (maximum of five contact attempts) and email. Facilities that performed upper-digestive endoscopy, colonoscopy, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) and/or echoendoscopy procedures in adult patients were considered eligible for inclusion in the study.

As a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, several facilities were operating under reduced activity or had research restrictions. These facilities did not provide consent to participate in the study, therefore reducing the a final sample size to 10 establishments.

During visits to participating facilities, the study’s importance and relevance were explained and participants’ consent was obtained. A semistructured questionnaire was distributed based on the guidelines applicable to endoscopy facilities12,15,16 and validated through a pilot study. The pilot study was conducted in three facilities with the application of the tools used in the study. The results were evaluated by the authors, and changes to improve data collection were made. The pilot study facilities were excluded from the final sample.

The questionnaire was administered through an interview with the personnel responsible for processing endoscopes, followed by an inspection of supplies for the specific brushes used for cleaning endoscopic channels/lumens.

The following aspects of the cleaning process were evaluated by the interview conducted by the main researcher:

- Structural conditions and compatibility in the use of brushes

- Criteria for purchasing brushes and the type of brushes purchased (disposable or reusable)

- Criteria and periodicity for disposal and replacement of brushes

- Reuse protocols for brushes Brushes were visually inspected for presence of wear, presence of soil, and whether the structural condition of brushes had changed (e.g., bent or other irregularities). The data were subsequently entered into a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet and descriptive statistical analysis was performed by analysis of the frequency and mean distribution.

Results

The 10 facilities that were visited performed the following procedures: upper-gastrointestinal endoscopy (UGE; one of 10); UGE and colonoscopy (three of 10); UGE, colonoscopy, and ERCP (five of 10); and UGE, colonoscopy, ERCP, and echoendoscopy (one of 10).

All facilities were located within hospitals. Of the 10 facilities, four were public, two were philanthropic, and four were private. Of the four private facilities, three were outsourced clinics, meaning they were not managed by the hospital. The average number of procedures performed by the facilities per month was 264 (range 100–775).

Only one facility subjected its devices to automated cleaning and disinfection by automated endoscope reprocessor after manual cleaning. Manual cleaning was performed exclusively in nine of 10 facilities. The facilities had an average of 9.8 endoscopes available for use (range 2–26).

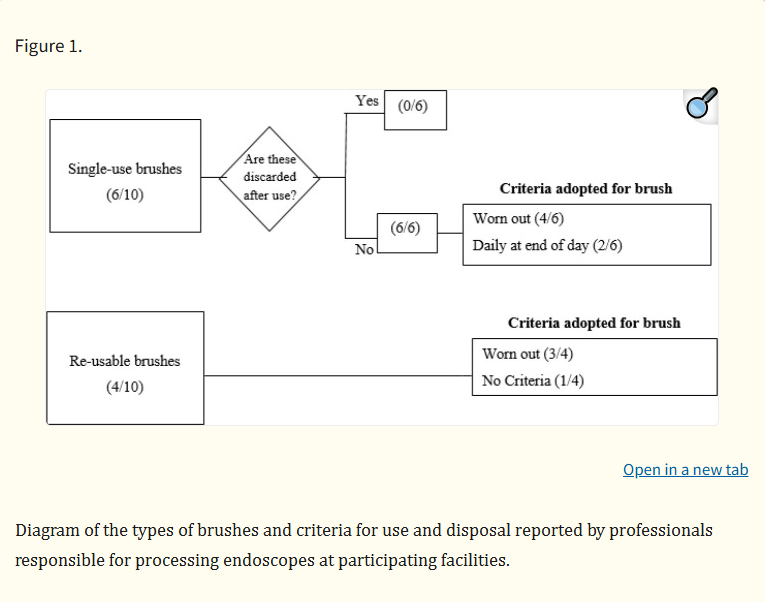

The use of brushes for internal friction of the endoscope channel was used in all facilities. However, full immersion of the equipment during brushing was verified in only one facility. In five facilities, only one design of brush was observed. This was a conventional long-bristle brush with one or two heads. The others had a conventional long brush with bristles and another short one with two heads for cleaning valves. Figure 1 summarizes the types of brushes (disposable or reusable) and the criteria for use and disposal in facilities.

Only one facility among the seven that reported disposing of brushes once they were worn out characterized the wear. This facility considered the absence of bristles on the brush head to warrant disposal, while other facilities did not mention assessing specific wear patterns.Regarding the brushing technique performed, brushing in seven of 10 facilities occurred until the brush exited the distal tip without visible residue; therefore, the number of brush passes varied based on the observation of residue on the brush. The three other facilities established different protocols for brushing: one determined a minimum of three brushings, one a minimum of five brushings, and one a minimum of 10 complete brushings, regardless of the absence of visible residue.Most of the facilities (eight of 10) reported cleaning bristles before introducing or returning the brush to the channel. However, all of these facilities performed the bristle cleaning with water, despite most endoscope instructions for use (IFUs) advising the use of detergent solution.13 The other facilities (two of 10) did not perform any type of cleaning of brush bristles.No facility described using a routine cleaning, disinfection, or sterilization protocol after processing each endoscope, regardless of the use of reusable or disposable brushes. Among the facilities that used disposable brushes (six of 10), two discarded the brushes at the end of the shift, one sterilized brushes in hydrogen peroxide plasma sterilizer at the end of the day, one performed high-level disinfection at the end of the day, and two did not perform any type of brush treatment. Regarding reusable brushes (four of 10), two facilities performed daily cleaning in enzymatic detergent, one sterilized the brushes at the end of the day, and one did not conduct any treatment.

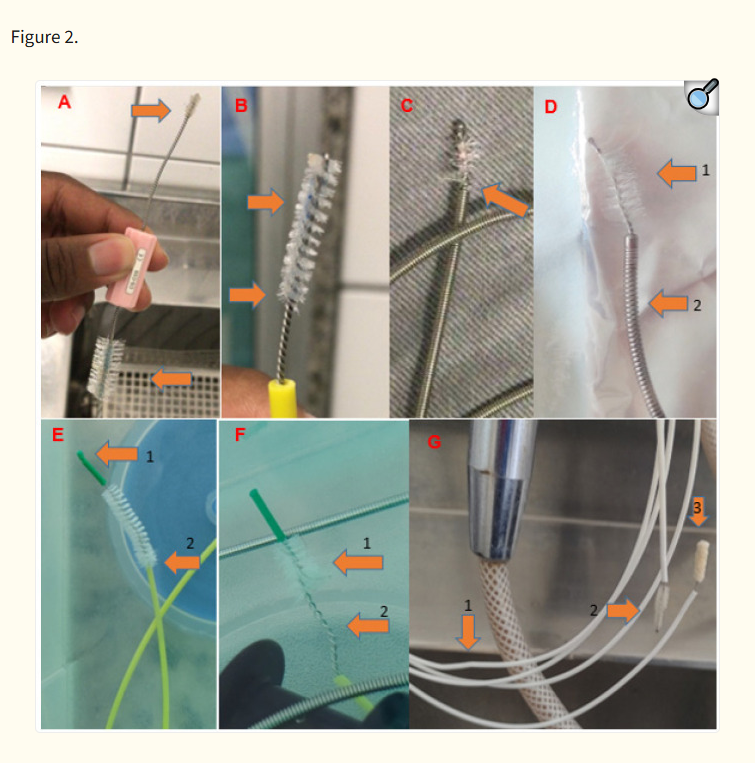

The brushes in use in all facilities were considered to be in good condition by the users. However, the use of new brushes with no sign of wear and tear was only observed in two facilities, and these were disposable brushes. Irregularities in the structure of the brushes were observed, regardless of whether disposable or reusable brushes were found. Figure 2 shows the types of alterations found, such as lack of bristles, crookedness, and wear.

The brushes in use in all facilities were considered to be in good condition by the users. However, the use of new brushes with no sign of wear and tear was only observed in two facilities, and these were disposable brushes. Irregularities in the structure of the brushes were observed, regardless of whether disposable or reusable brushes were found. Figure 2 shows the types of alterations found, such as lack of bristles, crookedness, and wear.

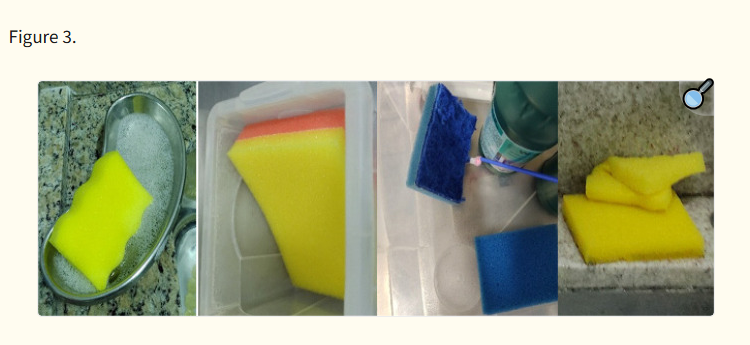

Images of the brushes in use at endoscopy clinics participating in the study. A: Valve cleaning brush with dirt and wear on both heads. B: Valve cleaning brush with dirt and wear. C: Reusable brush with wear and evident lack of bristles. D1: Reusable brush with absent and worn bristles. D2: Brush cable ring wear. E1: Disposable brush with failure in the continuity of the tip. E2: Disposable brush with signs of wear. F1: Disposable brush with presence of hair on bristles. F2: Absence of bristles on the head of the brush and crookedness on the extension of the head. G1: Disposable brush with crookedness on the handle extension. G2: Worn bristles. G3: Sponge head with moisture retention.Despite not being an objective of this study, it was observed that some facilities used sponges or brushes dedicated to the external cleaning of endoscopes in the internal cleaning of channels. These materials, such as sponges with an abrasive layer for household use, were used (four of 10; Figure 3). These sponges have the potential to detach lint and retain moisture, which differs from the manufacturers’ recommendations and increases the risk of adverse events in patient care. In fact, endoscope manufacturer IFUs generally recommend the use of clean, lint-free cloths, brushes, or sponges for the external cleaning of endoscopes.13

Discussion

Reducing the risk of contamination by effectively processing flexible endoscopes is a global concern.7,11,15 Cleaning the channels with friction (usually with a brush) is a fundamental step for cleaning the channels of this equipment and an important part of the process for safely returning these instruments to patient care.2,17

It is necessary for manufacturers to validate the manual cleaning process due to the variability of materials and methods, as well as the variety of medical equipment types. Regarding brushes, manufacturers should advise users on the specifications for size, type, quantity, design, and steps to be followed to achieve effective cleaning. Of note, more than one brush model may be indicated for cleaning certain equipment.1,7,10

Although shortcomings can be found in endoscope manufacturers’ IFUs, such as missing information, lack of completeness or details, and inadequate specifications, guidelines related to the diversity of brushes used for cleaning endoscopes are available.11–13 Despite this, the use of a single model or brush size for the channel was evidenced in the facilities studied, which interferes with brushing effectiveness because the bristles need to contact the channel walls. Brushes of varying diameter are indicated for cleaning different endoscope channels and other equipment in clinical practice.10–12,17–19

The use of disposable brushes should be encouraged because they can reduce the risk of transmitting microorganisms and generally are in a better condition compared with reusable brushes.7,11,12,15 However, our results showed that even brushes marketed as disposable after a single use were being reused in the facilities studied. This increases the risk of damage and contamination and diverges from the purpose of single-use brushes, which are not designed or validated to be used repeatedly or to be processed.13

A lack of well-defined criteria regarding when to dispose of reusable brushes compromises the brushing process.10,18 When protocols for disposal of brushes do not exist, the technicians performing the cleaning may subjectively decide when to dispose. Despite the analysis in this study of poor brush condition in eight facilities (some of which were in a very poor state of use), all processing professionals judged that the brushes were in a suitable condition for use.

These observations reinforce that disposal criteria for the reuse of brushes must be detailed and well defined to prevent the use of defective brushes. Brushes should not have missing bristles or bends, which can put the structure of the equipment at risk, regardless whether the brushes are disposable or reusable.7,10,20,21

Another important aspect is the lack of care during brush use, which compromises the safety of an important processing stage. Bronzati et al.18 demonstrated how introducing brushes into the channels without cleaning the head at each outlet, followed by bristles being returned to the channels, makes cleaning ineffective. In their study, this action only reduced contamination by 10% in the channels compared with cleaning the bristles at each outlet, which reduced contamination by approximately 80%. Therefore, this essential task often is neglected in practice.

Our results showed that brushes with visible soil and in precarious use condition (with, for example, incomplete bristles or damaged and crooked handles) were found in the facilities. These brushes, which are not suitable for use, can cause damage to endoscopes and result in soil and microorganisms being in channels, providing an environment for the formation of biofilms.20–22

Faced with the risk of not eliminating residues from the channels, another concern would be transferring these residues or microorganisms to other equipment to be cleaned later with the same brush.5,23 Therefore, it is evident that daily care of brushes is not sufficient to guarantee safety, as performed in best-case scenarios. Current U.S. standards and guidelines state that brushes should be single-use (preferred) or cleaned and decontaminated between each use.7,15 Reusable brushes should be subjected to at least a manual cleaning and high-level disinfection after each use. In addition, an inspection to evaluate the presence of bends, lack of bristles, wear, or other damage should be carried out before reuse.11,12,15

Infectious and noninfectious adverse events appearing in the Food and Drug Administration’s Manufacturer and User Facility Device Experience (MAUDE) database demonstrate evidence of contamination from reuse of disposable brushes.24–26 In addition, pieces of components of the brushes (e.g., tip heads) have been reported to come loose and remain trapped inside endoscope channels, subsequently reaching the patient’s cavity. These data support the importance of using well-functioning cleaning brushes and have implications for patient safety.24–26

Factors that can influence the cleaning of flexible endoscopes in endoscopy facilities include the need for short turnaround times, a reduced number of professionals and equipment, and lack of exclusive personnel for cleaning endoscopes due to scarcity of financial resources. In addition, a lack of training and standardized guidelines related to the importance of care during and between uses of reusable brushes, as well as criteria for disposal, shows an indifference to brushes, thereby increasing risks of contamination.7,9,23

We observed the use of household sponges with an abrasive surface or those that allowed lint to detach during use and accumulate moisture. These sponges can cause damage to the equipment surface, and pieces can migrate into the interior channels of the endoscopes and transfer to the patient.25,26 In addition, they can facilitate microbiological multiplication due to contact with a high microbiological load, a lack of processing of brushes for reuse, and moisture accumulation, thereby reducing endoscope processing safety.14,25

This study had important limitations, including the small sample size, which may not represent the totality of endoscopy facilities. However, due to the high frequency of reuse of disposable brushes, the lack of care in decontamination, and undefined criteria for disposal of the brushes found in this study, we can infer that this is a common practice with a latent need for change. Another limitation was that microbiological analysis of the brushes in use was not performed, which would allow a more detailed analysis of the risk of contamination.

Endoscopy facilities are encouraged to take a critical look at the care of supplies used in practice. In the case of reusable brushes, they must demonstrate adequate structural condition and be decontaminated after each use. This reduces the risk of transmission of microorganisms and helps prevent the transfer of soil between equipment.

Conclusion

The use of improper brushes and sponges and the lack of criteria for the reuse and disposal of reusable brushes were evidenced in this study, which indicates the urgent need for improvement in the acquisition and care of the materials involved in endoscope processing.

Following recommendations of published guidelines and manufacturers’ IFUs is essential to ensuring effective processing of flexible endoscopes. In addition, facilities should have established protocols for inspection and disposal, conduct detailed training and competency programs, perform internal audits of established protocols, and provide tools for maintaining processing quality and reducing contamination risks and damage to endoscopes.

Discussion

Reducing the risk of contamination by effectively processing flexible endoscopes is a global concern.7,11,15 Cleaning the channels with friction (usually with a brush) is a fundamental step for cleaning the channels of this equipment and an important part of the process for safely returning these instruments to patient care.2,17

It is necessary for manufacturers to validate the manual cleaning process due to the variability of materials and methods, as well as the variety of medical equipment types. Regarding brushes, manufacturers should advise users on the specifications for size, type, quantity, design, and steps to be followed to achieve effective cleaning. Of note, more than one brush model may be indicated for cleaning certain equipment.1,7,10

Although shortcomings can be found in endoscope manufacturers’ IFUs, such as missing information, lack of completeness or details, and inadequate specifications, guidelines related to the diversity of brushes used for cleaning endoscopes are available.11–13 Despite this, the use of a single model or brush size for the channel was evidenced in the facilities studied, which interferes with brushing effectiveness because the bristles need to contact the channel walls. Brushes of varying diameter are indicated for cleaning different endoscope channels and other equipment in clinical practice.10–12,17–19

The use of disposable brushes should be encouraged because they can reduce the risk of transmitting microorganisms and generally are in a better condition compared with reusable brushes.7,11,12,15 However, our results showed that even brushes marketed as disposable after a single use were being reused in the facilities studied. This increases the risk of damage and contamination and diverges from the purpose of single-use brushes, which are not designed or validated to be used repeatedly or to be processed.13

A lack of well-defined criteria regarding when to dispose of reusable brushes compromises the brushing process.10,18 When protocols for disposal of brushes do not exist, the technicians performing the cleaning may subjectively decide when to dispose. Despite the analysis in this study of poor brush condition in eight facilities (some of which were in a very poor state of use), all processing professionals judged that the brushes were in a suitable condition for use.

These observations reinforce that disposal criteria for the reuse of brushes must be detailed and well defined to prevent the use of defective brushes. Brushes should not have missing bristles or bends, which can put the structure of the equipment at risk, regardless whether the brushes are disposable or reusable.7,10,20,21

Another important aspect is the lack of care during brush use, which compromises the safety of an important processing stage. Bronzati et al.18 demonstrated how introducing brushes into the channels without cleaning the head at each outlet, followed by bristles being returned to the channels, makes cleaning ineffective. In their study, this action only reduced contamination by 10% in the channels compared with cleaning the bristles at each outlet, which reduced contamination by approximately 80%. Therefore, this essential task often is neglected in practice.

Our results showed that brushes with visible soil and in precarious use condition (with, for example, incomplete bristles or damaged and crooked handles) were found in the facilities. These brushes, which are not suitable for use, can cause damage to endoscopes and result in soil and microorganisms being in channels, providing an environment for the formation of biofilms.20–22

Faced with the risk of not eliminating residues from the channels, another concern would be transferring these residues or microorganisms to other equipment to be cleaned later with the same brush.5,23 Therefore, it is evident that daily care of brushes is not sufficient to guarantee safety, as performed in best-case scenarios. Current U.S. standards and guidelines state that brushes should be single-use (preferred) or cleaned and decontaminated between each use.7,15 Reusable brushes should be subjected to at least a manual cleaning and high-level disinfection after each use. In addition, an inspection to evaluate the presence of bends, lack of bristles, wear, or other damage should be carried out before reuse.11,12,15

Infectious and noninfectious adverse events appearing in the Food and Drug Administration’s Manufacturer and User Facility Device Experience (MAUDE) database demonstrate evidence of contamination from reuse of disposable brushes.24–26 In addition, pieces of components of the brushes (e.g., tip heads) have been reported to come loose and remain trapped inside endoscope channels, subsequently reaching the patient’s cavity. These data support the importance of using well-functioning cleaning brushes and have implications for patient safety.24–26

Factors that can influence the cleaning of flexible endoscopes in endoscopy facilities include the need for short turnaround times, a reduced number of professionals and equipment, and lack of exclusive personnel for cleaning endoscopes due to scarcity of financial resources. In addition, a lack of training and standardized guidelines related to the importance of care during and between uses of reusable brushes, as well as criteria for disposal, shows an indifference to brushes, thereby increasing risks of contamination.7,9,23

We observed the use of household sponges with an abrasive surface or those that allowed lint to detach during use and accumulate moisture. These sponges can cause damage to the equipment surface, and pieces can migrate into the interior channels of the endoscopes and transfer to the patient.25,26 In addition, they can facilitate microbiological multiplication due to contact with a high microbiological load, a lack of processing of brushes for reuse, and moisture accumulation, thereby reducing endoscope processing safety.14,25

This study had important limitations, including the small sample size, which may not represent the totality of endoscopy facilities. However, due to the high frequency of reuse of disposable brushes, the lack of care in decontamination, and undefined criteria for disposal of the brushes found in this study, we can infer that this is a common practice with a latent need for change. Another limitation was that microbiological analysis of the brushes in use was not performed, which would allow a more detailed analysis of the risk of contamination.

Endoscopy facilities are encouraged to take a critical look at the care of supplies used in practice. In the case of reusable brushes, they must demonstrate adequate structural condition and be decontaminated after each use. This reduces the risk of transmission of microorganisms and helps prevent the transfer of soil between equipment.

Conclusion

The use of improper brushes and sponges and the lack of criteria for the reuse and disposal of reusable brushes were evidenced in this study, which indicates the urgent need for improvement in the acquisition and care of the materials involved in endoscope processing.

Following recommendations of published guidelines and manufacturers’ IFUs is essential to ensuring effective processing of flexible endoscopes. In addition, facilities should have established protocols for inspection and disposal, conduct detailed training and competency programs, perform internal audits of established protocols, and provide tools for maintaining processing quality and reducing contamination risks and damage to endoscopes.